Facebook enables advertisers to promote content to nearly 900,000 people interested in “vaccine controversies”, the Guardian has found.

Other groups of people that advertisers can pay to reach on Facebook include those interested in “Dr Tenpenny on Vaccines”, which refers to anti-vaccine activist Sherri Tenpenny, and “informed consent”, which is language that anti-vaccine propagandists have adopted to fight vaccination laws.

Facebook’s self-serve advertising platform allows users to pay to promote posts to finely tuned subsets of its 2.3 billion users, based on thousands of characteristics, including age, location, gender, occupation and interests. In some cases, users self-identify their interests, but in other cases, Facebook creates categories based on users’ online activity. In 2017, after a controversy involving antisemitic interest categories, Facebook vowed to build “new guardrails” on its targeting categories.

Facebook is already facing pressure to stop promoting anti-vaccine propaganda to users amid global concern over vaccine hesitancy and a measles outbreak in the Pacific north-west.

On Thursday, California congressman Adam Schiff, the chair of the House intelligence committee, cited the Guardian’s reporting on anti-vaccine propaganda on Facebook and YouTube in letters to Mark Zuckerberg and Google CEO Sundar Pichai urging them to take more responsibility for health-related misinformation on their platforms.

“The algorithms which power these services are not designed to distinguish quality information from misinformation or misleading information, and the consequences of that are particularly troubling for public health issues,” Schiff wrote.

“I am concerned by the report that Facebook accepts paid advertising that contains deliberate misinformation about vaccines,” he added.

Facebook’s ad-targeting tools are highly valued by businesses because they enable, for example, a pet supply store in Ohio to show its advertising exclusively to pet owners in Ohio. But the tools have also spurred controversy.

A Russian influence operation took advantage of the self-service platform to promote divisive content during the 2016 US presidential election. In 2017, ProPublica revealed that the platform included targeting categories for people interested in a number of antisemitic phrases, such as “How to burn Jews” or “Jew hater”.

While the antisemitic categories found by ProPublica were automatically generated and were too small to run effective ad campaigns by themselves, the “vaccine controversies” category contains nearly 900,000 people, and “informed consent” about 340,000. The Tenpenny category only includes 720 people, which is too few to run a campaign.

Following the ProPublica report, Facebook removed many automatically generated targeting categories and said it was “building new guardrails in our product and review processes to prevent other issues like this from happening in the future.”

Facebook declined to comment on the ad targeting categories, but said it was looking into the issue.

“We’ve taken steps to reduce the distribution of health-related misinformation on Facebook, but we know we have more to do,” a Facebook spokesperson said in a statement responding to Schiff’s letter. “We’re currently working on additional changes that we’ll be announcing soon.”

The changes under consideration include removing anti-vaccine misinformation from recommendations and demoting it in search results, the spokesperson said. The steps they have already taken include having third-party fact-checkers review health-related articles.

A YouTube spokesperson also declined to comment on Schiff’s letter, but noted the company’s recent changes to its recommendation algorithm to reduce the spread of misinformation, including some anti-vaccine videos.

“We’ve done a number of things within this realm,” the spokesperson said. “But these are still early days. And our systems will get better and more accurate.”

Competing echo chambers

In the past, Facebook has suggested that simply censoring anti-vaccine propaganda might be less effective than counter-speech providing accurate information.

But a pro-vaccination activist whose non-profit organization, Voices for Vaccines, uses Facebook to promote positive messages about vaccination to parents, questioned the efficacy of counter-speech on the topic.

“I’m not interested in promoting the idea that vaccines are controversial,” said Karen Ernst, who runs Voices for Vaccines from her home in St Paul, Minnesota, and budgets from $50 to $100 each month to advertise pro-vaccine content on Facebook.

Ernst said that she was well-aware of the “vaccine controversies” interest category, but never uses it. Targeting people who see vaccines as controversial “gets toward making social media a place where vaccines are fought over, which feels really counterproductive to public health,” she said. “It’s making the echo chamber more echo-y.”

Ernst said that while she believes Facebook advertising can be an effective means of promoting vaccination, she feels outgunned by anti-vaxxers. Many of her advertisements have been rejected because she has not registered as a political advertiser, she said, in part out of concern that Facebook’s new transparency tools for political advertising will make her a target for harassment from anti-vaxxers. (The tools would identify Ernst as having paid to promote the posts, and maintain an archive of her ads.)

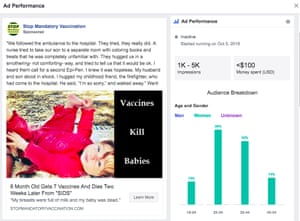

Larry Cook, a Californian who runs an anti-vaccine Facebook group with more than 150,000 members, has raised more than $7,700 on GoFundMe to fund anti-vaccine misinformation Facebook advertisements since 29 January. Cook has raised nearly $80,000 total on GoFundMe for anti-vaccine promotion since 2015. On GoFundMe, he claims that he has spent more than $35,000 on Facebook advertising over four years.

Cook’s advertisements have been censured by the UK advertising regulator, the Advertising Standards Authority, but continue to run in the US, where he is currently focused on targeting mothers in Washington state – the site of a current measles outbreak.

Ernst said one way Facebook could help combat anti-vaccine propaganda would be to provide free advertising to public health organizations promoting sound medical advice.

Schiff first introduced a House resolution declaring “unequivocal congressional support for vaccines” in 2015. He told the Guardian by phone that he plans to introduce a similar resolution again this year, but that he may update it to feature “the role that these social media companies are playing in the propagation of this bad information”.

“It’s difficult to understand why, when this problem has been raised, why either company would take advertising dollars to promote dangerous and misleading information,” he said. “I think our chances of passage are far better than they have been in the past, and tragically that’s because we’ve seen the problem just grow and grow.”